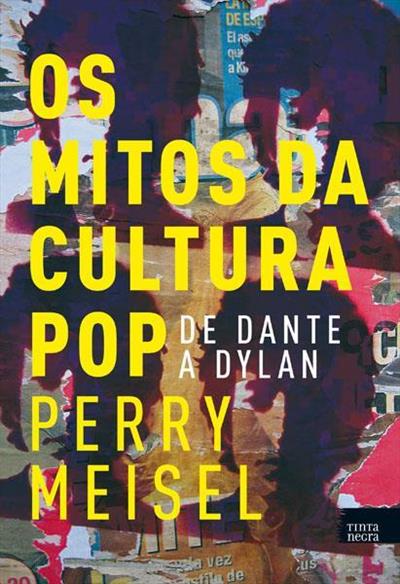

by Perry Meisel

Friends and Apostles: The Correspondence of Rupert Brooke and James Strachey, 1905-1914. Edited by Keith Hale. Illustrated. 304 pp. New Haven: Yale University Press. $35.

Rupert Brooke is remembered less for his poems than for his good looks and less for his good looks than for the way he abused his friends with them. On the receiving end first and longest among the men and the women Brooke loved before his death from blood poisoning en route to the Turkish front at Gallipoli in 1915 was James Strachey, the younger brother of Lytton Strachey and the future translator and editor of Freud. Although Brooke's correspondence was published in 1968, the exchange of letters between Brooke and Strachey was excluded by its editor, Geoffrey Keynes, one of Brooke's moralizing Cambridge friends. Now Keith Hale, an assistant professor of English at the University of Guam, has edited and introduced the correspondence with skill and thoroughness. It is almost impossible to read it without sensing Brooke's and Strachey's vivid feeling for each other and the extent to which the bond between them structured their lives. It will no longer be possible to speak of either one separately.

Brooke and Strachey met at Hillbrow School in 1897 when each was 10. They were extraordinarily competitive. In 1901, Brooke returned to Rugby, where his father was a housemaster; Strachey returned to his large family in London, where he became a day boy at St. Paul's. As Strachey had ardently hoped, he and Brooke were reunited at Cambridge in the autumn of 1906. There they made the passage from being precocious, overeducated English schoolboys to being self-impressed Cambridge undergraduates who did not even consider the question of their own identities until their election to the Apostles, or Cambridge Conversazione Society, the secret organization that had been created at midcentury to counter Oxford's control of English taste, and that now included Lytton Strachey and John Maynard Keynes among its principal members.

These are love letters as well as missives of two Apostolic friends (indeed, the relation between lust and friendship was often among the topics of Apostolic discussion), and they flesh out, often in rough-and-tumble detail, what was regarded as a perfectly open way of life, even when both turned to the pursuit of women. While Strachey is ordinarily cool and rationalistic, he is, as a lover, fervent and passionate. And while Brooke is customarily ardent and passionate, he is, as a lover, demure and condescending. ''It's your soul that I long for,'' Strachey writes in 1909. ''We will not be sentimental about anything,'' Brooke replies, ''except nobility.'' The sadism lasts until the end, even though Strachey grows more relaxed and secure. Brooke, however, grows more and more unsettled, quarreling with Bloomsbury and wandering in America and the Pacific. ''I've loved you all the time,'' Strachey writes in 1913. A month later, Brooke replies, ''You'd better go on hating me.''

Despite Hale's exhaustive editorial work, his volume sheds little new light on Brooke as a poet. Like most critics, Hale believes that the jingoistic masterstrokes of Brooke's famous war sonnets represent a turn away from the ''decadent stance'' of Brooke's youth, even though their sharp relation to death and exile also makes them continuous with High Romantic schoolboy poems like ''The Bastille.'' Nor does Hale deal with Strachey's work. Translating Freud meant exchanging his older brother's authority for that of an even greater ironist, and letting fresh air of his own into Bloomsbury's pantry. Psychoanalysis gave Strachey an escape from English tradition that Brooke could not find, allowing him to reinvent its Romantic premises rather than trying to reimagine them.

Originally published in The New York Times Book Review, January 17, 1999